Paul Cohen: The Chicago Jew Behind Country's Nashville Sound

Today, it is difficult to think about American country music without immediately thinking of Nashville Tennessee, a city that has been considered the capital of country music since the 1950s. If Nashville is considered by many to be the “Mecca of country music,” then the Country Music Hall of Fame is surely its Kaaba. As one walks through the self-described “soaring, majestic” Hall of Fame Rotunda, familiar names stand out, including Hank Williams (both Senior and Junior), Waylon Jennings, Patsy Cline, Merle Haggard, Willie Nelson, Charley Pride, Dolly Parton, and even the King of Rock n’ Roll himself, Elvis Presley.

During a recent visit, though, it was another name caught my attention: Paul Cohen. This name would likely not have garnered a second thought somewhere else, like at the Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame, where there are quite a number of Jewish inductees. But to be frank, up until that trip, I had never associated Jews with country music, other than the many Jews who consider themselves fans of the genre. It turns out, however, that it would be difficult to tell the story of the history of country music – and specifically the “Nashville sound” that popularized country music and turned it into what it is today – without talking about Paul Cohen, a Jew from Chicago. In fact, it is unlikely that Nashville would be considered the “Music City” that it is known as today without Cohen’s efforts.

When fellow Country Music Hall of Fame member Johnny Cash announced Cohen’s posthumous induction into the Hall of Fame in 1976, Cash introduced Cohen as a “pioneering recording executive who was one of the first producers to begin recording here in Nashville and was instrumental in creating and developing the Nashville sound.” Similarly, the Hall of Fame itself describes Cohen as “one of the men chiefly responsible for Nashville’s emergence as a country music recording capital,” noting that Cohen was at the Hall of Fame for its opening in 1967 (Cohen was indeed the president of the Country Music Association that year).

Cohen was born to a Jewish family in Chicago on November 10, 1908. He began working in the music industry in the late 1920s when he joined Columbia Records. Around the same time, an English businessman named Edward Lewis started Decca Records in Bristol, England. By 1934, brothers Jack and Dave Kapp – fellow Chicago Jews – had started Decca’s American operations and hired Cohen to serve as the label’s midwestern branch manager, where he was based out of Cincinnati Ohio and was responsible for finding and signing new talent. By the mid-1940s, Cohen moved to New York where he was put in charge of Decca’s “hillbilly” music section, as the genre was then known (it become popularly known as “country music” several years later).

Although he soon became one of the most well-known and highly respected producers in Nashville, Cohen didn’t actually live there at the time, although he did eventually move to Nashville after starting his own record label in the late 1950s. During the 1940s and most of the 50s, however, he lived in New York and would travel frequently to Nashville, staying for a month at a time at the Andrew Jackson Hotel, where musicians and others who knew he was in town would flock to see him and attract his attention. According to his 1970 obituary, Cohen once said he produced records in Nashville “because he liked the atmosphere of the South, the charm of the people and, particularly, the ease with which its musicians made their music.” (the Jewish population in Nashville in 1948 was approximately 2,900, out of a total population of over 167,000, under 2%).

During an early visit to Nashville, Cohen met producer and musician Owen Bradley, who by that time had become a regular on Nashville radio. In 1947, Cohen hired Bradley to open Decca’s Nashville office and to run their Nashville recording sessions at Bradley’s Castle Studios, which at the time was located in Nashville’s Tulane Hotel. During this time, none of the major record labels had a presence in Nashville and they were reluctant to create one. As time went on, the efforts of Cohen and Bradley were “rapidly transforming [Nashville] from a Southern outpost to an established music hub to rival New York, Los Angeles and Chicago.”

It was the session musicians hired for Decca recording sessions that, under Cohen and Bradley’s supervision, “created what became known as the Nashville sound.” In 1955, when Cohen was contemplating moving Decca’s country music operations to Dallas, Texas, Bradley convinced Cohen to stay in Nashville by promising him to build a new recording studio that met all of Cohen’s specifications.

During the 1950s and 60s, Cohen signed some of the biggest names in country music to Decca, including Webb Pierce, Pee Wee King, Kitty Wells, and Patsy Cline. Pee Wee King described Cohen as “a fine man, a great producer, director, and A&R man,” who “had a stable of performers that read like a Who’s Who in the record business.” During her hall of fame induction speech (which occurred the same day as Cohen’s posthumous induction), Kitty Wells thanked Cohen, stating she would not have been where she was without him. One author noted that “Cohen is remembered for an energetic production style – as much cheerleader as executive—and a knack for spotting new artists and matching them with songs (often published by his own publishing companies).”

Another author, describing the influence that Cohen, Bradley, and a few others had on the Nashville Sound, noted that in crafting the genre, they “expunged the embellishments of honky tonk and stripped it of its country referents by replacing the fiddle with violins, rebuilding rhythm sections with pianos, vibraphones, and drums, all the while moving accompaniments upscale to the smooth sounds of vocal groups.” The Encyclopedia of Country Music says that Cohen, Bradley, and the musicians at their studio created “a hotter, more exciting sound.”

While Cohen appears to have been well liked among his recording artists, there may have been at least one notable exception: Buddy Holly. In 1955, Holly, then 19 years old, signed a deal with Cohen’s Decca Records. However, Holly soon became frustrated with Decca and Owen Bradley’s production style; in particular the lack of autonomy that Holly was given as an artist. After an especially tense recording session, several of Holly’s recordings, including a recording of the now timeless “That’ll Be the Day,” were cut from his upcoming record and shelved.

In February 1957, Holly called Cohen and asked to be released from his Decca contract and allowed to re-record the shelved songs. Cohen allegedly rejected Holly’s requests, reminding him that Decca owned his music and could do anything they wanted with it. Apparently undeterred, Holly traveled to Clovis, New Mexico and re-recorded “That’ll Be the Day,” which was then released by Brunswick Records under his band name, The Crickets, as opposed to his own name, in an apparent attempt to get around his contractual restrictions. When Cohen and the other executives as Decca found out about Holly’s scheme, they were initially furious but soon calmed down after they realized that Decca actually owned Brunswick. Eventually, of course, “That’ll Be the Day” became an international hit, cementing Holly’s place as a Rock n’ Roll legend, even long after he died in a plane crash two years later at the age of 22; a day cemented in popular culture as “the day the music died.” Years later, Rolling Stone Magazine named “That’ll Be the Day” as the 39th greatest song of all time.

At least one author who has written about the Jewish influence on Nashville’s music scene – Stacy Harris – seems to suggest that even though Cohen was eventually inducted into the hall of fame six years after his death, at least one of the reasons he was not inducted while he was alive was because he was Jewish. According to Harris, “[w]hile most individuals are usually inducted during their lifetimes, the CMA waited a full six years following Cohen’s 1970 death before granting him that honor.” Harris also notes that “of the twenty-five Country Music Hall of Fame inductees preceding Cohen, only one alive at the time of the first inductions [1967] was inducted posthumously.” While this author has uncovered no evidence either way, Harris’ theory certainly seems plausible.

Cohen died from complications of cancer in Bryan Texas on April 1, 1970, the third anniversary of the opening of the Country Music Hall of Fame. A week after his death, Nashville’s Music Row offices (“the entire industry” in Nashville) closed for 30 minutes to pay tribute and hold a memorial “for the man who started it all.” His obituary in the Tennessean newspaper stated that Cohen was “widely credited with being the music businessman most responsible for the rise of Nashville as a recording center.”

Paul Cohen Country Music Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, 1976.

Sources:

- HARRIS, STACY. “Kosher Country: Success and Survival on Nashville’s Music Row.” Southern Jewish History, Journal of Southern Jewish Historical Society, 1999.

- HOFSTRA, WAREN. “Afterword: The Historical Significance of Patsy Cline.” Sweet Dreams: The World of Patsy Cline. Univ. of Ill. Press.

- The Country Music Hall of Fame, www.countrymusichalloffame.org.

- ROSENBERG, NEIL and WOLFE, CHARLES. “The Music of Bill Monroe.” Univ. of Ill. Press, 2007.

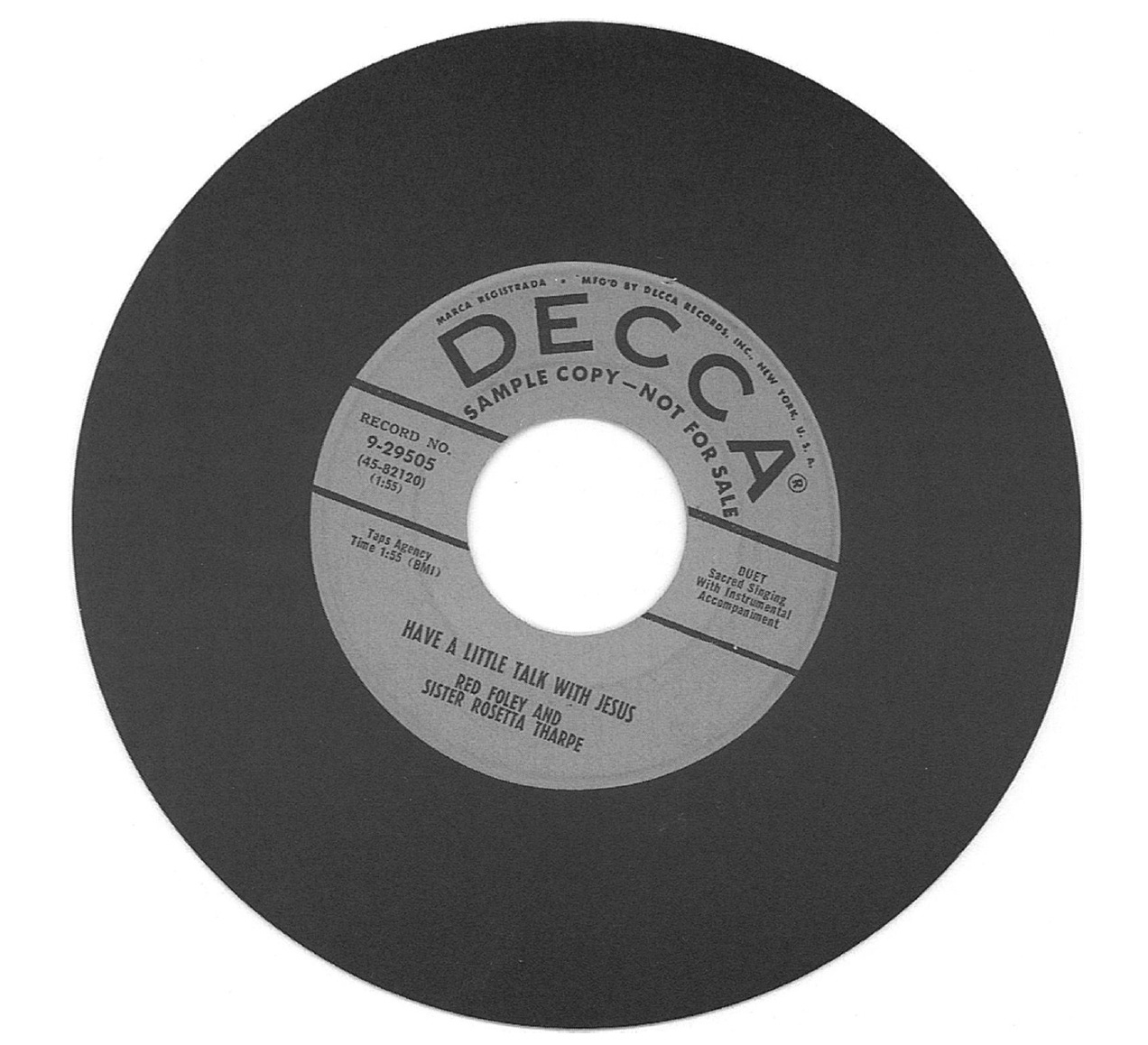

- WALD, GAYLE. “‘Have a Little Talk’: Listening to the B-Side of History.” Popular Music, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005.