BEFORE ISRAEL, THERE WAS ARARAT, A PROPOSED JEWISH HOMELAND IN…BUFFALO?

Grand Island is located literally in the middle of the Niagara River, just north of Buffalo and just south of Niagara Falls, in Upstate New York, on the United States-Canadian border. It is almost exactly 300 miles from New York City, as the crow flies. As of the 2020 census, its population was just over 20,000. Its entire area is less than 34 square miles.

Before the American Revolution, Grand Island was occupied by various indigenous peoples, including the Attawandaron and the Senecas. It became part of the British colonies in 1764, as part of the treaty that ended the French and Indian War. The State of New York purchased the island in 1815, for the sum of $11,000.

Although there has been at least some Jewish presence in and around Buffalo since the nation’s founding, it’s never been large. Today, the entire Buffalo metropolitan area—which includes Grand Island—has a total Jewish population of approximately 13,000; not exactly a booming Jewish metropolis. Buffalo’s first synagogue was established in 1848. At that time, the Jewish population was well less than 100 (and likely closer to 0 than to 50), out of a total of approximately 2,000 people (in fairness to Buffalo, at the time, there were only approximately 8,000 Jews in the entire United States).

Given this description, Grand Island New York would likely not be the first place that people thought of when, prior to the founding of the modern State of Israel, the Jewish people—who at that time had been living in the diaspora since the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans n 72 AD—were in search of a permanent home.

But this did not deter Mordechai Manuel Noah, a Jewish journalist, playwright, Tammany Hall politician, former ambassador, and even High Sheriff of New York. For it was there—on Grand Island between the two banks of the Niagara River—that in 1825, Noah proposed the city-state of Ararat, which he envisioned as a home for the world’s Jews. Or as he called it: “City of Refuge for the Jews.”

Noah was born in Philadelphia in 1786, 10 years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. His great-great-grandfather, Dr. Samuel Nunez, was one of the first Jews to arrive in the United States, fleeing Portugal during the Portuguese Inquisition. Dr. Nunez and his family arrived in Georgia with General James Oglethorpe, who would go on to found the Province of Georgia and become Georgia’s first governor. Dr. Nunez and his family were one of the founding families of Savannah.

According to one account [which I find a bit hard to believe, but have no proof either way], Noah was raised as an orphan, in poverty, but through hard work and some good luck and connections along the way, was able to pull himself out of the dire circumstances of his youth. Whether or not this was true, eventually, Noah became “one of the best-known men in New York.”

Approximately 9 years before “founding” the Jewish nation of Ararat, then- Secretary of State James Monroe abruptly removed Noah from his post as Consul to the Kingdom of Tunis (modern day Tunisia), to which he had been appointed by President James Madison a few years prior. In removing him from that position, Monroe stated that Noah’s Jewish religion was an “obstacle” to performing the functions of his role. This apparently “intensified [Noah’s] sense of Jewish identity.” According to one account:

Whilst a most tolerant and liberal-minded man in respect to the religious belief of others, he was strongly attached to his own people, regarding them as a race apart, originally chosen by God to work out a sublime faith, who, notwithstanding all they had undergone, were increasing in number and had a great future before them. He not only believed in the fulfilment of the prophecies , that they would come together again as a nation, but that the time in the world's history for the beginning of the movement had arrived, and that he, under Divine inspiration, was an appointed instrument to bring it about; for among all the successors of Israel and of Jacob that assembled in the synagogue, there was not one who was a more sincere believer or reverential worshiper.

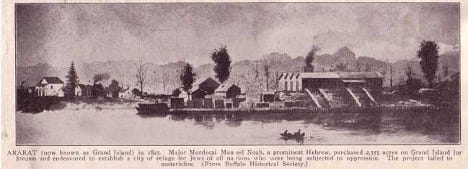

After being removed from his role as Consul, Noah settled in New York City, and eventually convinced Samuel Leggett—a wealthy banker and Noah’s friend—to purchase approximately one-fifth of Grand Island’s acreage. They paid just under $17,000 for approximately 2500 acres.

Mordechai Noah, undated

Several decades before Theodor Herzl—widely considered the “founder” of modern-day Zionism—was even born, and over 1700 years since the destruction of Jerusalem, Mordechai Noah planned to use the newly-acquired land to build a Jewish nation approximately 4 miles from the mouth of Lake Erie. His ultimate vision was to eventually purchase the remainder of Grand Island, “either as a permanent homeland or a temporary refuge until Palestine could be regained.”

1825 was quite an eventful year throughout the entire country, which was just shy of turning 50 years old. The country had only 24 states then, with a population of less than 12 million. In February of that year, after no presidential candidate received a majority of the electoral college votes in the 1824 presidential election, the House of Representatives elected John Quincy Adams to be president. He was sworn in a few months later.

Throughout most of the year, General Marquis de Lafeyette—the celebrated French military officer who served as a commander under George Washington in the American Revolutionary War—toured the country. General Lafeyette reached Buffalo in early June. And just 4 months later, the Erie Canal opened, connecting Albany to Buffalo and Lake Erie.

While all these exciting things were happening in Buffalo and throughout the country, unfortunately, the situation for the world’s Jews was much bleaker. In the Russian Kingdom—which at that time housed over 60% of the world’s Jewish population—Czar Nicholas I took power. Almost immediately, he instituted antisemitic laws—called the “Jewish Regulations,” including forcibly conscribing Jewish youth into the Russian military beginning at the age of 12 and forcing all Jews into the “pale of settlement,” where life for Russia’s Jews was restrictive and economically austere.

According to the Jewish Virtual library, Czar Nicholas I “sought to destroy all Jewish life in Russia, and his reign constituted a painful part of European Jewish history.” In the Jews’ ancestorial homeland of Israel, the Islamic Ottoman Empire was into its third (and what would turn out to be its last) century of rule. While there were some Jews living in Eretz Yisrael (land of Israel) at the time, there weren’t many, and the few who did live there did so at the mercy of their Islamic overlords.

It was with this backdrop that Mordechai Noah announced his new Jewish island nation. According to one of the very few accounts from a contemporaneous source—businessman and politician Lewis F. Allen, who would go on to purchase Grand Island in 1833, Noah’s intent was to “make a suitable asylum for the Jews of all nations, whereon they could establish a great city, and become emancipated from the oppression bearing so heavily upon them in foreign countries”

In recounting the story of Noah and the proposed City of Ararat several decades later, Allen described Noah in fairly flattering terms:

Physically, he was a man of large muscular frame, rotund person, a benignant face, and most portly bearing. Although a native of the United States, the lineaments of his race were impressed upon his features with unmistakable character [translation: “he looked Jewish”]; and if the blood of the elder Patriarchs or David or Solomon flowed not in his veins, then both chronology and genealogy must be at fault. He was a Jew, thorough and accomplished. His manners were genial, his heart kind, and his generous sympathies embraced all Israel, even to the end of earth. He was learned too, not only in the Jewish and civil law, but in the ways of the world at large.”

It likely goes without saying—considering he attempted to build a Jewish nation—

but Noah was also a proud Jew: “He was a pundit in Hebrew law, traditions and customs,” according to Lewis Allen. “‘To the manner born,’ he was loyal to his religion, and no argument or sophistry could swerve from his fidelity, or uproot his hereditary fate.” When someone asked Noah his opinion on Jews converting to Christianity, his response was that “modern Gentiles would sooner be converted to the Jewish faith, than that the Jews would be converted to theirs.”

In preparation for his new Jewish homeland, Noah planned a dedication ceremony, which was to take place on Grand Island on September 15, 1825. He announced his plans in the widely-circulated National Advocate—the official newspaper for the Tammany Hall political machine, for which he served as the editor. However, when the day arrived, he was told that there weren’t enough boats “to take the hundreds of people who would attend” from Buffalo to the island. As a result, the dedication ceremony for Ararat—Noah’s proposed Jewish homeland, which was to emancipate and liberate Jews from all corners of the world—was held at an episcopal church in Buffalo proper.

Many members of the public, the press, and even (maybe especially) his fellow Jews ridiculed Noah’s plan, questioning its ability to succeed. Undeterred, at the dedication ceremony, Noah addressed the crowd with what he called the “Jewish Declaration of Independence,” declaring himself “Governor and Judge of Israel.” And after appointing himself the first Judge of Ararat (he envisioned a new Judge every 4 years), he immediately began issuing edicts to Jews worldwide, and even attempted to collect taxes from them, at the rate of “three shekels in silver per annum, or one Spanish dollar.” It was the responsibility of every Jew worldwide, Noah apparently thought, to support his new Jewish homeland, whether they would live there or not.

He called for a census and a tax of Jews around the world, abolished polygamy among Asian and African Jews, and enjoined Jews in foreign lands to remain loyal “until further orders.” He named several European rabbis “commissioners” of Ararat, to assist in carrying out his proclamation.

One of the more bizarre aspects of his already very bizarre speech was when he commanded the Native Americans—who he said, “in all probability [were] the descendants of the lost tribes of Israel”—to “be informed of their lineage and reunited into the Jewish race.”

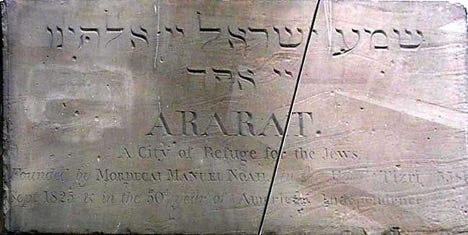

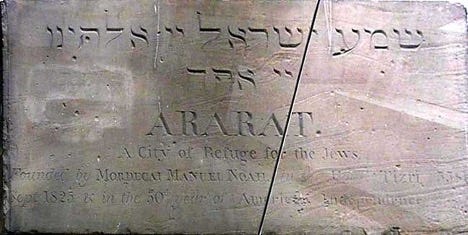

Major Noah—as he was called—had a cornerstone inscribed for the Ararat dedication ceremony. Above the name “Ararat. A City of Refuge for the Jews,” where the words of the holy Hebrew prayer, the Shema (translated into English as “Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.”) It was laid at the same Episcopal church that hosted the dedication ceremony. Noah apparently had an obelisk built of brick and wood to hold the cornerstone.

Photo of the Ararat Cornerstone

The Buffalo Patriot, Extra was on site for the dedication ceremony, and reported the following:

It was known, at the sale of that beautiful and valuable tract called Grand Island. That it was purchased, in part, by the friends of Major Noah of New York, avowedly to offer it as an asylum for his brethren of the Jewish persuasion, who, in other parts of the world, are much oppressed…

We are gratified to perceive . . . that coupled with this colonization is a Declaration of Independence, and the revival of the Jewish government under the protection of the United States,--after the dispersion of that ancient and wealthy people for nearly two thousand years, and the appointment of Mr. Noah as first Judge.

They also published the ceremony’s order of procession:

Notwithstanding what seems to be a well-attended grand dedication ceremony, and despite Noah’s passion, dedication, and vision, the Jewish nation-state of Ararat would never come to be. From a 1975 article in the New York Times:

Noah left Buffalo a few days later, leaving no one near Grand Island to put his ideas into operation. There was no Jewish settler even living in Buffalo until 10 years after Noah left.[1]

Noah had no religious or secular authority in the Jewish community to enforce his “orders,” and the Jews of Eastern Europe never learned of his provisions for them.

Noah’s friend Lewis Allen later attributed the failure of Ararat to “two grand mistakes” in Noah’s plan: (1) that he had no power or authority over the Jewish people, and (2) “he was utterly mistaken in their aptitude for the new calling he proposed them to fulfill” [translation: they were too stupid to follow his plan.]

This was, in fact, the whole affair. The foreign Rabbis denounced Noah and his entire scheme. . .. But, having no confidence in his plans or financial management, the American Jews, even, repudiated his proceedings; and, after a storm of ridicule heaped on his presumptuous head, the whole thing died away, passed among the other thousand-and-one absurdities of other character which had preceded it.

According to another account: “The celebration in Buffalo was the beginning and the end of the scheme. The European Rabbis refused to sanction it. The proclamation was not responded to. The monument of brick and wood, like the project itself, fell to pieces, and in the course of years wholly disappeared.”

Major Noah went on to become a judge, married “a wealthy Jewess of high respectability,” raised a family, and died in 1851. Lewis Allen purchased the land on Grand Island in 1833, where he opened a timber mill. Allen eventually obtained Noah’s cornerstone, and placed it on the Island, where it stayed for another 17 or so years. Eventually, it was gifted to the Buffalo Historical Society, and it has been on display in the Buffalo Town Hall for the last 60 or so years.

It would be another 123 years before the Jewish people had a land to call their own, approximately 6,000 miles away from Grand Island and Ararat, the Jewish city that never was.

[1] It’s unclear whether this is accurate, as other estimates say that Buffalo had “less than 100” Jews at the time. Either way, there certainly weren’t a lot of Jews in Buffalo at the time.

References:

The Founding of the City of Ararat on Grand Island, Speech by Hon. Lewis F. Allen, March 5, 1866. Published by Cornell University Library.

Dr. Samuel Nunez’s Escape from the Inquisition, Dr. Yitzchok Levine, Homodia (Oct. 2010).

The Settlement of the Jews in North America, Charles P. Daly, 1893.

https://www.nytimes.com/1975/09/15/archives/dream-of-jewish-state-near-buffalo-is-recalled.html

https://buffaloah.com/h/jews/index.html#:~:text=The%20census%20of%201850%20lists,this%20prompted%20others%20to%20leave%2C